Municipal governments across the country are beginning to consider local strategies responding to the new Opportunity Zones created as part of the federal tax reform package last year, which are expected to leverage about $6 trillion in capital gains by recycling them into new business and real estate investment in about 8,700 low-income Census tracts across the country. That makes Opportunity Zones the largest federal community development program, with implications everyone is still trying to comprehend.

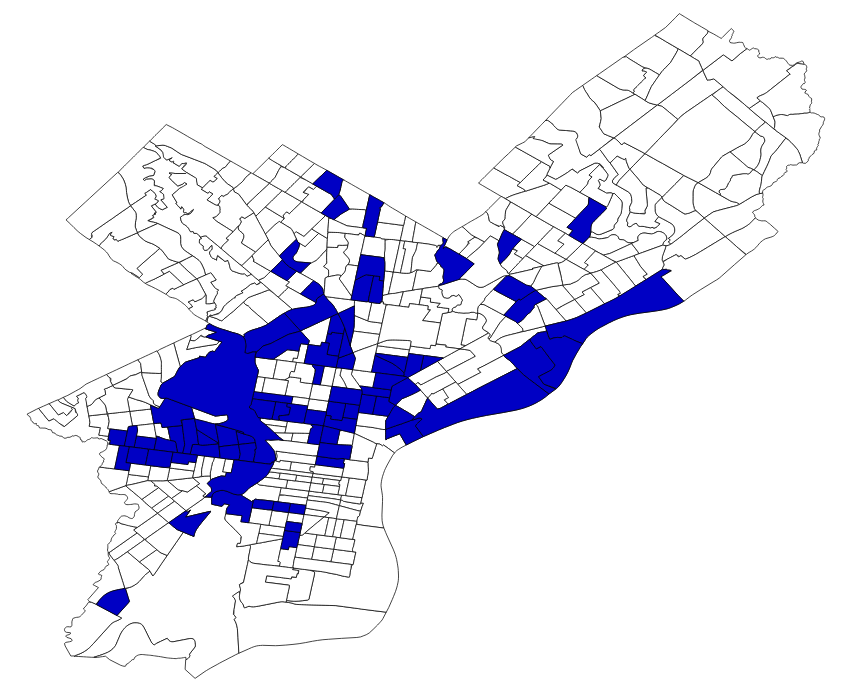

We previously wrote about a Lindy Institute report outlining the different dimensions of this issue that local policymakers should be thinking about, since the federal government provided no guidance on local policy, and PIDC has released some broad concepts for how Philadelphia will approach its Zones, which were selected by Governor Wolf this year. The real estate analytics company Stepwise also published an informative post looking at the attributes of Philly's Zones.

The latest entry in this space comes from Smart Growth America, in a new report ranking the 8,700 Opportunity Zones on their prospects for attracting walkable urban development—as opposed to more land-hungry sprawl—and also on their propensity to engender social equity or their risk of attracting unmanaged gentrification.

Read the report for more on their methodology, but the essential point of the study is to make the case for investors to utilize these zones to create more of the kind of walkable urban neighborhoods that America is facing an acute shortage of, and also to alert local governments to the need for proactive policy to ensure that the stated mission of the Opportunity Zones is achieved, lifting up current residents, businesses, and cultures, rather than displacing them. The report ranks the top Zones based on Smart Growth Potential (SGP) index and a new Social Equity + Vulnerability Index (SEVI) to highlight the most sensitive cases for policymakers.

The following passage is a good summary of the report's premise:

For any revitalization effort, land use and impact matters. Since the 20th century, the dominant US land use and economic development strategy promoted the creation of drivable sub-urban real estate - sprawl. This land use and development pattern has led to neighborhoods and municipalities with higher infrastructure and maintenance costs, greater physical inactivity, poorer quality of life, and higher greenhouse gas emissions which lead to climate change. However, starting in the 1990s, demand for smart growth and walkable communities has overtaken its auto-oriented counterpart, because residents and business enterprises want to locate in places that take a different approach to land use and development. People in the United States are demanding vibrant communities with affordable housing and transportation options, and a great sense of place and community.

These communities – walkable urban places – generally have higher economic performance, greater social equality, positive health impacts and lower greenhouse gas emissions. Based on the 2016 Foot Traffic Report, there are significant and growing rental rate premiums for walkable urban office (90 percent), retail (71 percent), and rental multi-family (66 percent) over drivable sub-urban products. Combined, these three product types have a 74 percent rental premium over drivable suburban. But because we have built so few of these types of places, existing walkable communities that have a great sense of community and local culture are extremely vulnerable to the pent-up market demand that could lead to unmanaged gentrification and displacement.Communities of color and low-income neighborhoods in Opportunity Zones want greater investment that not only brings economic revitalization, but also preserves and strengthens current residents, business and cultures, instilling value in people rather than displacing them. Despite Opportunity Zones’ transformative potential, the authorizing legislation and proposed regulations for Opportunity Zones do not contain any guardrails or social impact requirements that ensure that investments neither crowdsource displacement or accelerate climate change or the negative socioeconomic impacts by repeating the land use and development mistakes of the 20th century. Therefore, understanding which Opportunity Zones with investable projects and businesses and community informed and community driven policy frameworks are best positioned to create vibrant, inclusive walkable communities is critical to the overall success of the initiative.

One extremely disappointing finding from SGA's analysis of the Census tracts selected by state Governors is that "98% of the designated Opportunity Zones scored less than the minimum score of 10 to be determined a Smart Growth Potential (SGP) Opportunity Zone," according to their ranking system, while only 2% of the designated zones scored a 10 or higher.

"The majority of the the designated Opportunity Zones could be described as low density, drivable suburban areas with significantly higher housing and transportation costs, higher greenhouse emissions and lower quality of life...While 13% of Opportunity Zones with Smart Growth Potential with scores less than 10 are rural, the vast majority of Opportunity Zones with limited smart growth investment potential are in small towns, suburbs, and urban areas. For these communities, aggressive federal, state and local policies are needed to retrofit auto-oriented urban form and revitalize rural town centers into the vibrant and inclusive communities that Americans are demanding."

The good news is that Governor Tom Wolf appears to have done a good job choosing Opportunity Zones in Pennsylvania, at least from SGA's perspective, because Philadelphia and a few sites in Pittsburgh and the Lehigh Valley all get high ranks for smart growth potential. In order, the highest ranking states were New York, California, New Jersey, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Ohio. In Philadelphia, the Opportunity Zones with the highest potential to support investment in walkable urban development were "Center City East" (really, Callowhill), University City, South Broad Street and Snyder, Fairmount, Northern Liberties/Fishtown, and "Center City West" (where it's unclear if they're referring to the tracts covering Francisville or Point Breeze.) As we mentioned in the prior post about Opportunity Zones, the selections are based on 2010 Census data, which resulted in some odd selections of neighborhoods that would not be widely considered low-income in 2018.

In Philadelphia, the Opportunity Zone with the highest Social Equity and Vulnerability Index score, perhaps not surprisingly, is the University City Census tract. Here are the criteria they use for this:

For tracts with high Social Vulnerability Index scores, SGA recommends local officials "immediately prioritize place and people-based 'do no harm policies' that protect vulnerable residents and business and incentivize new supply of attainable housing and commercial spaces."

What does that look like? These are some of the policies SGA says officials should be considering in Opportunity Zones with high Vulnerability scores:

The good news in Philadelphia is that we're off to a decent start on a number of these items. These maps from Aaron Bauman of the University City and Callowhill Opportunity Zones highlight the multi-family and mixed-use zoning categories that are eligible for City Council's new Mixed-Income Housing bonus program, which provides additional height and density for developers to offset the cost of providing below-market-rate units, or paying into the Housing Trust Fund. The fact that these areas are zoned primarily for multi-family housing also means they're well-prepared to absorb a lot of housing demand in the face of increased investment activity. That's preferable to a strict zoning scenario like on South Broad Street where neighborhoods would see only inflated land prices but few new dwellings created.

That's not to say enough has been done, especially not for renters, who still have few significant protections or much public policy support to speak of from the City, but considering the proven effectiveness of local programs like LOOP and other property tax deferral programs at preventing displacement, we're off to a decent start before anyone's really started forming a policy response to the Opportunity Zone challenges.

Showing 1 reaction

Sign in with

Facebook