/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-pmn.s3.amazonaws.com/public/ORXE2CXAPZHITC7GZZSNGT2EGM.jpg)

(Image: Philadelphia City Council)

One of the big-picture trends of housing politics over Mayor Kenney’s two terms so far has been a significant transfer of power over land use and planning from the institution of the Mayor, to the institution of City Council.

Mayor Kenney and his team have seemed very disinterested in joining this fight from their side throughout his time in office to preserve the Mayor’s important powers in this area. The result has been a steady march of legislation and norm-breaking behavior by Council that is leaving the next Mayor with substantially less power over housing outcomes in the city than even the minimal amount it had before.

This is a very bad political situation from the perspective of anyone who wants to see the city get ahead of our housing affordability issues in a serious way, improve jobs and transportation access at a city and regional scale, or build in some more fairness around questions about which neighborhoods are being expected to fulfill the need for new homes in our growing city, and which aren’t.

One of the ways in which the institution of the Mayor influences housing outcomes is through appointments to the various Boards and Commissions established in the city Charter, which vote on approvals for various types of land use and building plans, with some of those decisions actually being binding (Art Commission) and some not (Planning Commission.) This is an area where the institution of the Mayor has a lot of power without involvement from City Council.

That is important because City Council—and particularly the District Council members—have a tremendous amount of power over issues like zoning and land use that play a key role in shaping housing outcomes, and there are only so many cards that the Mayor has to play to counter the worst of the Councilmanic Prerogative system governing City Council’s approach.

Any land use or built environment issue that ends up under Council’s control is governed by the unwritten law of Councilmanic Prerogative, where Council members are expected to give unconditional unanimous support to other members on their district bills, with the expectation that everyone else will be given the same courtesy. This unquestioned mutual back-scratching approach effectively puts one single individual in charge of land use outcomes within a whole Council district, with predictably bad outcomes. Three former District Councilmembers have gone to prison in the recent past over abuses related to Prerogative, but even when there’s no out-and-out illegal behavior involved, it’s still the case that some of the most corrupting aspects are fully legal.

The upshot of all this is that taking more kinds of decisions away from the Mayoral administration, and putting them into the Prerogative basket, could be expected to increase the scope for corruption and ensure that citywide goals for affordability, housing and jobs access, and climate change will continue to lose out in a death-by-a-thousand-cuts from a million more localized concerns. That’s the wrong direction for the city to go in at this moment when we need strong citywide leadership on so many different fronts when it comes to housing our growing population.

But that is the direction a majority of City Council continues to push in, with almost no pushback from the Kenney administration. In the latest episode in this series, Council President Darrell Clarke introduced a Charter change amendment Friday that would expand the number of seats on the Zoning Board of Adjustment from 5 to 7, create defined roles and professions that must be represented on the board, and also introduce a requirement that City Council vote to approve the Mayor’s Zoning Board of Adjustment appointees going forward. Ryan Briggs at PlanPhilly reports on the proposed amendment:

“If approved, the ZBA would be required to include an urban planner, architect, zoning attorney, a real estate finance expert, and two members from community organizations. The legislative language also states “all members shall have a demonstrated sensitivity to community concerns regarding the protection and character of Philadelphia neighborhoods.” The current bylaws do not mandate any specific qualifications or expertise.

Currently, the board is chaired by public affairs consultant and former city councilmember Frank DiCicco, who took over after his successor was ensnared in a corruption case involving electricians union leader John Dougherty. Two other members –– Confesor Plaza and James Snell –– have ties to local building trades unions, while board member Thomas Holloman works as an architect. Vice chair Carol Tinari serves on the boards of several civic organizations and is married to local defense attorney Nino Tinari. The Director of Planning and Development also serves as an alternate for absent members.”

Creating defined roles is a pretty reasonable idea and one we’ve written favorably about in the past. This is how it already works for the Art Commission and the Historical Commission, so it’s not unusual for Philly. The addition of two seats for community members also makes a lot of sense, as such groups currently play a big role in the city’s process, but have had uneven representation on the ZBA.

Unfortunately, the prescribed roles don’t capture the full range of perspectives that need to be included. Most notably, while there are two representatives from the building trades on the current ZBA, Council President Clarke’s proposal doesn’t even have one dedicated labor seat.

Attorney Lauren Vidas says on Twitter she’s heard the Laborers District Council allegedly has “great concerns” about the charter change, and it seems likely other building trades unions will have similar concerns as the ZBA has long been a board where the trades have a lot of influence. Recall that before the current ZBA Chair Frank DiCicco held that position, Mayor Kenney had appointed Jim Moylan, an ally (and chiropractor) of IBEW Local 98 Business Manager Johnny Doc, who had also been the head of the Pennsport Civic Association, and was active in zoning matters on the Delaware waterfront.

In addition to Labor, the new set of Board roles would also be incomplete without representation for Communitive Development Corporations (CDCs), commercial corridor organizations, or tenants, and Council should consider adding even more roles to the proposed list to ensure those perspectives are considered.

The Council approval requirement and the references to a “demonstrated sensitivity to community concerns regarding the protection and character of Philadelphia neighborhoods” give away the game that this is a warning shot to the ZBA from Council President Clarke and other more conservative-on-housing Councilmembers that he wants to see them stop approving multifamily housing.

Clarke would like for the ZBA decisions to be more like a popularity contest, and fall in line with the local letters from those opposing new buildings. But while there is some gray area to this, it's important to understand that the ZBA is more like a court, and has legal parameters to follow based on state law and case law. And the state case law is a lot more expansive in what it considers to be a "hardship" worthy of a zoning variance than what Council President Clarke and other ZBA detractors would prefer to see.

Especially in the last 2 years, Council President Clarke has been going to increasingly extreme measures in his War on Housing, trying every tool in the shed to rezone more areas in the 5th District for single-family-only housing, increase costly and archaic parking mandates for new homes, and push more and more building projects into the more politicized zoning variance process. In essence, he’s been trying to make it harder to build common building types in compliance with the code, so that local builders and contractors then have to seek out special permission from the city where Clarke and those who share his approach can have more influence over approval.

That kind of discretionary approach, however, makes any kind of true planning impossible, and creates a corrupting process that is excessively political, and undermines the city’s big-picture goals on affordability, access, and climate.

Importantly, this kind of approach also leads directly to the large caseload at the Zoning Board that Council President Clarke and others have complained about.

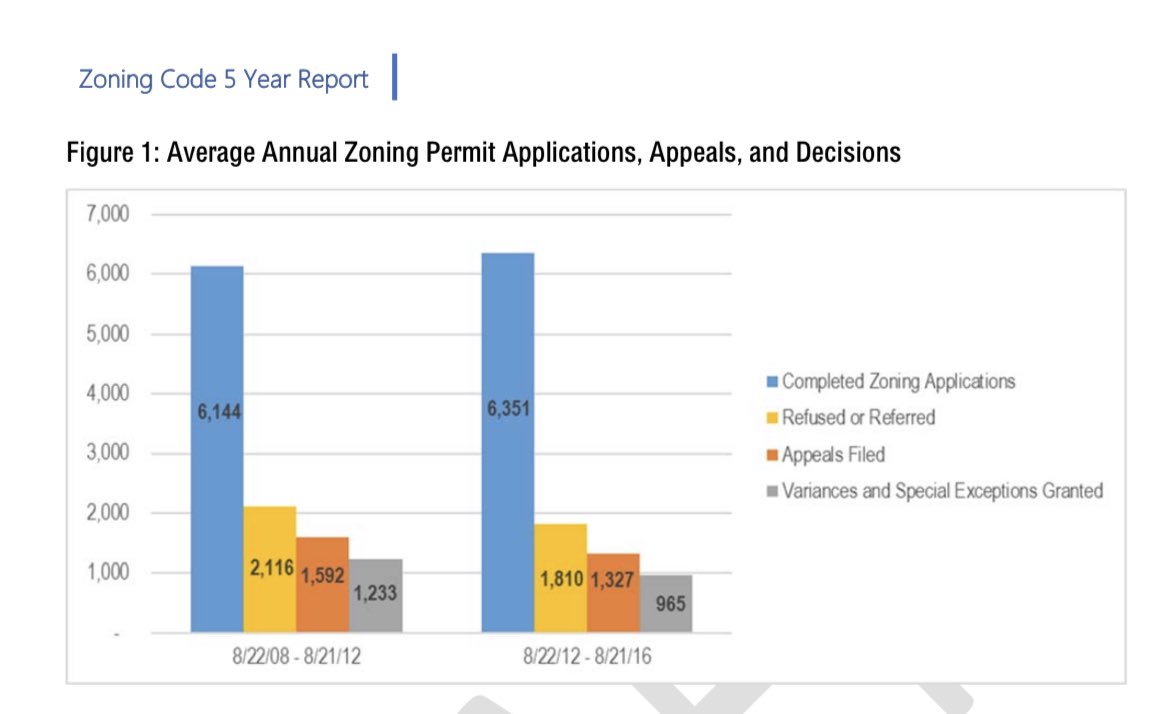

The Planning Commission’s 2018 review of the first five years of zoning activity after the passage of the historic Zoning Code Commission reform package in 2012 found essentially that City Council’s moves to try and inhibit small multifamily buildings in areas mostly zoned for single-family homes account for a very significant portion of the variance activity. In the areas zoned for small multi-family buildings, variance activity was more than cut in half between 2012 and 2016, showing that if you get the code language right (as Council and Planners did for RM-1), you get fewer variance requests.

Lifting the bans on these ‘Missing Middle’ housing types—as President Biden's HUD has urged local governments to do—would be one simple way to reduce the caseload at the ZBA, but Council President Clarke has been taking the exact opposite approach, trying to make it even harder to create any new multi-unit housing, and cut off the possibility of getting a variance for this from the ZBA. Last year Council President Clarke even tried to create an overlay district where the ZBA wouldn’t be allowed to approve a variance for multi-unit properties, which likely wouldn’t hold up in court, but it gives a sense of how committed he is to a One-Size-Fits-All vision for housing in Philadelphia.

It’s unclear that the new Council approval requirement would ultimately mean very much in terms of real-world consequences, but the housing-skeptical intent behind it matters because it’s emblematic of the misguided views on housing and zoning that prevail among some members of City Council, which are showing up in more consequential pieces of legislation.

Locally, there are good practical reasons for Council to stop devoting so much energy to managing the density phobia of a few, and embrace the opportunity to have more, and more varied, housing in the city. For one thing, earlier this week, Council members were just celebrating the release of the spending plan for the $400 million Neighborhood Preservation Initiative, which is financed by a bond underwritten by new construction tax.

The plan seems like it will make a positive difference, and what would be great is if members looked for more ways to raise more new construction tax money, rather than less.

The success of the NPI program now depends on how much construction spending happens in the city, so under those circumstances, there should start to be some more resistance from political supporters and beneficiaries of NPI spending initiatives to any Council moves that would clearly reduce the amount of construction tax revenue.

It’s also important because Philadelphia needs a lot more jobs coming out of the COVID recession, especially ones that don’t require a college degree. The pandemic has wiped out almost all the job gains from the last decade of growth, so anti-growth politics especially now are really a luxury we can’t afford.

Construction jobs are good working-class jobs and even entry-level work pays well, and the NPI program is going to help put more people to work. But we are going to badly miss out on the full economic power of NPI if this Council continues to try and have it both ways on housing and jobs.

Showing 1 reaction

Sign in with

Facebook