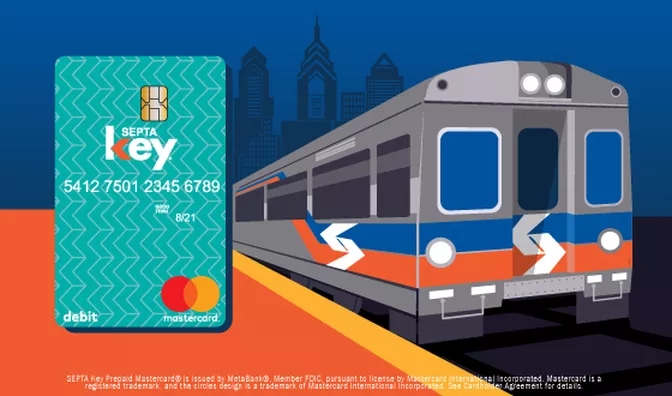

(SEPTA is already going to do a version of public banking | Image: SEPTA)

SEPTA Key implementation achieved some new milestones in the past month, with the Zone 4 regional rail rollout, elimination of paper transfers, and now, the apparent introduction of prepaid debit card features that could function as a basic checking account for some riders.

One of the more interesting and lesser-known Key features is that riders will eventually be able to use it like a prepaid debit card, and even deposit their paychecks onto their SEPTA Key card.

People used to having a bank account wouldn't use this feature, but there are a lot of Philadelphians who are unbanked, and use high-fee check-cashing services for their banking needs. This is a bad deal for low-wage workers, and one of the more underrated things that can help put people on a path to financial stability is access to some plain-vanilla banking services.

By providing such a plain-vanilla debit card service, SEPTA Key—and ultimately SEPTA—could become the default banking option of choice for many un-banked riders.

Jim Saksa at PlanPhilly did a deep dive in many of the issues and implications of the prepaid debit card service, including some of the fees associated with different uses.

The MasterCard-branded Key Card will do almost everything a checking account does: accept ACH transactions and transfers from other credit or debit cards; allow direct deposits; use ATMs to withdraw cash, and; make retail purchases online and in person. The one thing it won’t do: cash checks. For that, Key holders will need to go to a check cashing service, which often charge between 1 and 4 percent in fees [...]

While everything related to SEPTA Key’s “transit wallet” will remain free, there will be some fees associated with the GPR, “retail wallet” account. If a personalized Key cardholder wanted to use the GPR account, she would face a $4.95 per month fee. That monthly fee would be waived, however, if one of two conditions were met: the holder made 20 or more qualified transactions in a given month, or directly deposited $650 or more in a given month.

SEPTA officials say they paid close attention to the political blowback over surprise fees in Chicago when a similar feature was rolled out on the Ventra card in 2013, and have aimed to keep them lower and more predictable. Ventra's prepaid debit feature has since been eliminated.

SEPTA has already started displaying ads about this feature and introducing the concept to riders, so it's probably not too far off. Saksa reported it would be rolled out after the retail vending machine network was in place.

This is of interest for a couple reasons. First, left activists have been talking about the prospect of forming a public bank for Philadelphia as a campaign issue, and here we are about to roll out something that is pretty much that—at least from the customer's point of view.

A 'public option' for banking is a good idea, since people living paycheck-to-paycheck don't have much need for more than a simple checking account, and about a third of people in Philadelphia are sadly in that position. Postal banking was a hot topic around 2014 when conversations about the finances of the Postal Service and bank regulation were in the news, as a way to both shore up the Postal Service's finances, and provide simple checking and savings accounts to the un-banked and under-banked. It's also a good way to undercut some of the predatory financial services that market to low-wage workers.

In the same way, it could make sense for SEPTA to become more like a credit union over time, managing both the prepaid debit card deposits, and perhaps eventually other institutional deposits. (Would this make SEPTA a version of the elusive "Infrastructure Bank?")

As this process is already in motion, it might make sense for activists interested in a public bank to focus their efforts on pushing SEPTA further in this direction. SEPTA isn't going anywhere, and they're already rolling out a whole retail network of kiosks, so people will be able to purchase the debit cards anywhere. The network is going to have a pretty big reach all over the city and region, which is something a standalone public bank would also need to have. Why reinvent the wheel?

SEPTA is also an appealing public bank option because its reach is regional, not just confined to Philadelphia, and could potentially come to manage deposits for entities across the region. I'm not familiar with all of the reasons people want to create a public bank, so perhaps this idea doesn't check every single box, but it seems like SEPTA is going to be offering a pretty similar service to what is typically envisioned for postal banking. Their distribution network for transit banking is regional and the infrastructure network for it is going to have a regional reach.

And most interestingly, getting the votes on the SEPTA board to make moves in this direction is actually neatly tied together with the cause of electing Democratic majorities at the state and municipal level in the suburban Counties, since that is who nominates people to the SEPTA board, along with the Governor. It's unclear what an approval process for a public bank would involve if not SEPTA-based, or if that route would be politically easier, but its at least worth considering riding on what SEPTA's already doing in this space.

To stay in the loop on political news, events, and updates from Philadelphia 3.0, sign up for our email newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Be the first to comment

Sign in with

Facebook