A little-noticed provision in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act created what could potentially be a powerful new financing stream for investment in real estate, business formation, and other commercial development in selected lower-income areas called Opportunity Zones, and a new policy brief from the Lindy Institute's Metro Finance Initiative is the first paper to develop some principles for what a local policy response should look like if we're expecting a much larger stream of investment capital into certain neighborhoods.

What is an Opportunity Zone?

Opportunity Zones, a brainchild of bipartisan duo, Senators Corey Booker (D-NJ) and Tim Scott (R-SC), leverage the capital gains from existing investments to fund new capital investments in specific rural and urban low-income Census tracts. The provision allows investors to reduce or eliminate their capital gains taxes on prior investments by reinvesting those gains into Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs) which must invest 90% of their assets into businesses and properties in designated areas.

Each state was given a certain number of low-income Census tracts they could designate, and Governors have already selected the sites. The Treasury Department is still finalizing the rules for this provision of the tax code, but there's already a lot of buzz about it because many financial observers seem to believe this will create a new multi-billion dollar pot of financing for urban development projects.

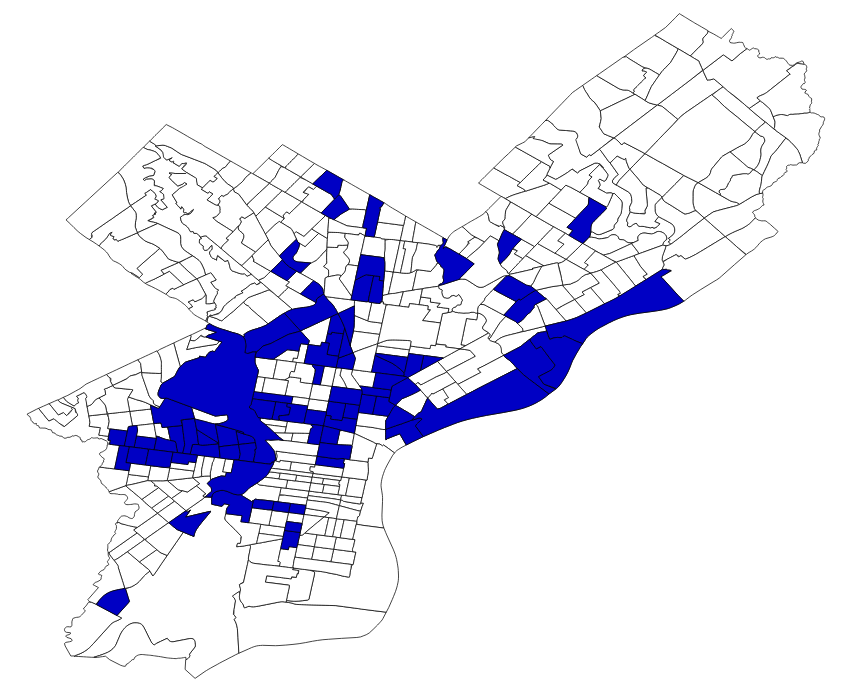

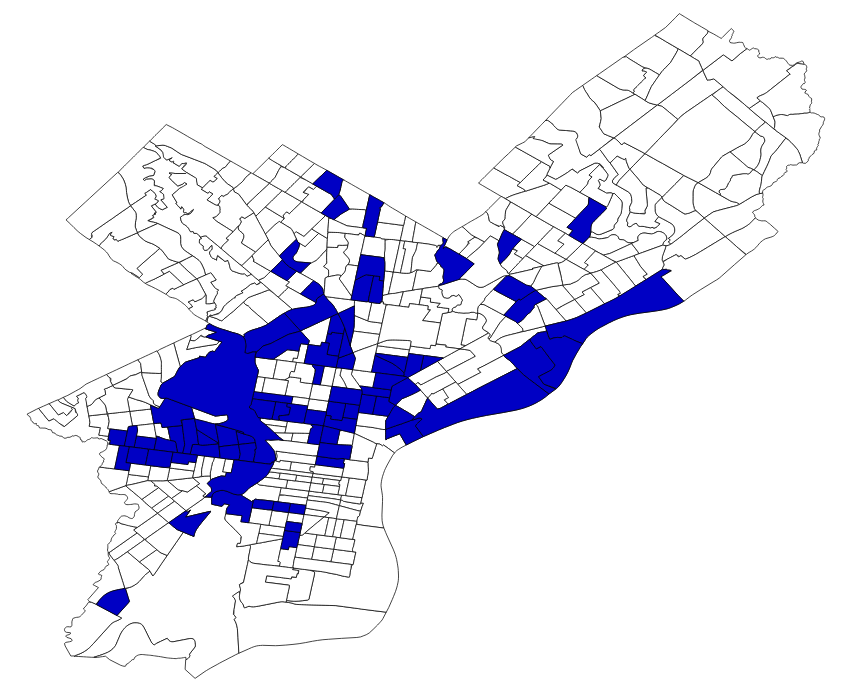

Where are the Opportunity Zones?

Because states used 2010 Census numbers as a baseline for what constituted low-income Census tracts, many of the tracts included seem curiously high-income today—places like the core of University City, Fishtown, and Callowhill are on the list, despite having nearly completed the cycle of gentrification since 2010.

(Image: Stepwise)

On the one hand, there are places that definitely could use more tax-advantaged capital investment than some of the places selected. But on the other hand, there's a good case for using these incentives to support and extend existing economic momentum, or encourage more investment in places near higher-education institutions, medical campuses, commercial corridors, or good transit and park infrastructure.

It could also lead to some bigger thinking on projects already in planning in some of the stronger market zones. Developer Eric Blumenfeld, best-known for restoring the Divine Lorraine, just decided to scrap a prior plan for a single-story retail strip at Broad and Spring Garden and build a big 30-story tower instead as a result of this area being included in an Opportunity Zone, so we can probably expect to see more of this type of thing happening. This is a great outcome in a place like Broad and Spring Garden which is right next to a Broad Street Line station and the Community College of Philadelphia and still has a lot of blight and vacancy despite its comparatively close proximity to Center City.

Read this Stepwise post for a further look at some of the market characteristics of the different Opportunity Zones selected by the Wolf administration.

What Should Local Governments Do to Plan for this Now?

The Lindy Institute's Metro Finance Lab released the first paper to address this topic, called "Transactions to Transformation: How Cities Can Maximize Opportunity Zones" by Bruce Katz of Brookings and Drexel's Evan Weiss looking at what local governments should do to plan for this new reality. A local role isn't spelled out in the federal legislation, and the only sub-national government role prescribed was for states to select the Opportunity Zone Census tracts.

But of course, local governments have an immense amount of power over things like land use, public infrastructure, and local economic development conditions that will go a long way toward shaping what ultimately gets built within each of the Opportunity Zones. There's a lot to unpack, but these high level principles are a good guide to the scope of what they say local governments need to be thinking about, and what's covered in the report.

Luckily for Philadelphia, the Planning Commission is wrapping up the last of the Philadelphia 2035 District plans this fall, and we now have lots of great data about the local economies, public priorities, and a detailed inventory of the local public and private assets for all corners of the city. Planning and City Council continue to work on remapping the zoning for different neighborhoods with varying levels of cooperation from the different District Councilmembers. And the Land Bank, while still reportedly pretty discretionary and loaded down with Council politics, has at least done the work of managing our information about the publicly-held properties that exist, and can now incorporate Opportunity Zone considerations into their current strategic planning process.

The full report is only 39 pages so give the whole thing a read. Here are a few early takeaways and some local policy context we should be thinking about as more people discover this powerful new program.

Update the Earlier Philadelphia 2035 Plans

Lindy recommends city governments put together an investment prospectus with all the relevant information about the local economies within the different Opportunity Zone Census tracts, and the District Plans and the recent economic research completed for Amazon HQ2 provide the City with a major head-start on this. Some of it needs a refresher though, and a more up-to-date set of assumptions for the next five years.

For example, the Central District plan, between Girard and Washington, river-to-river, was adopted all the way back in 2013, so it's been five years since it was updated. This part of the city has seen its job numbers and housing demand run far ahead of the 2013 projections, so if we keep following the plan and the resulting zoning recommendations, we're proactively planning to have a housing shortage.

Since there are several Opportunity Zones within this area, including the area around Spring Garden, that could drive additional demand it's time to revisit this, and any of the other early ones adopted that have significant Opportunity Zone coverage.

Finish Zoning Remapping, and Revisit Finished Maps in Opportunity Zones

City Council and the Planning Commission are still working through zoning remapping for the neighborhoods that have yet to be remapped. Maps are supposed to be informed by what's in the aforementioned District Plans, which cover multiple neighborhoods. The point of zoning remapping is to proactively plan at a more fine-grained level for the land use patterns we want to see in all of the city's different neighborhoods.

If we think that the designation of Opportunity Zones makes it more likely that OZ sites could see development proposals sooner, then Council and Planning should move those places up in the queue over the next couple of years, to make sure that the kind of projects getting funding are well-planned, locally beneficial, and that a rule-based by-right process is the norm.

Planning should also take a fresh look at already-completed zoning maps and not consider them off-limits for amendments to better take advantage of the Opportunity Zone status. Even if neighborhood rezonings were recently completed, the existence of the Opportunity Zones should lead us to reevaluate whether the choices made will be sufficient to accommodate a stepped-up level of housing and business investment. This especially matters in higher-opportunity neighborhoods in already-gentrified places within the Zones, which should accommodate their fair share of any new housing to avoid having not-yet-gentrified neighborhoods shoulder the entire responsibility.

Increasing zoned density in areas best-positioned to support more jobs and housing is one of the more powerful levers that local government has to ensure that these federal tax incentives translate into a lot of new construction activity in Opportunity Zone tracts that already have strong housing and job markets.

Capture Some of the Property Value Windfall in Opportunity Zones

As the authors write, "the presence of Opportunity Zones now gives cities more leverage to negotiate pricing and terms with developers to increase that land’s value upon sale," and the same is actually true for any property owner who owns some land in these zones now.

By designating certain land tracts eligible for a special tax break, the federal government has gone and made a lot of people's land more valuable overnight. That's going to create some speculative value for land in the places where the tax break is active, and eventually it's going to show up in property values, just like being in a well-regarded elementary school catchment shows up in property values. How can local government best use some of that new speculative value as a revenue stream to fund local services?

A split-rate property tax is a precision tool for doing exactly this. Property owners already have their assessments broken out into different values for land and buildings, but we tax both of these values at the same rate. Under Pennsylvania state law, Philadelphia as a Home Rule county has permission to create a split tax rate, with two separate tax millage rates for land and buildings. For example, in Allentown, PA they tax land at 5 times the rate for buildings. Most of the twenty-one PA local governments who do this choose to tax land at a slightly higher rate than buildings, rather than having solely a land tax (although Altoona did for a few years recently.)

In the Opportunity Zones, since it's specifically land and not buildings that will take on more speculative value, we need that separate land millage rate to target it. The recent Housing Action Plan from the Kenney adminstration set a goal of introducing new "value capture" methods to capture speculative land value increases when properties are upzoned, and split-rate property taxes are the same tool we'd need there too.

This idea also has contemporary political appeal in light of the debates over changes to the 10-year tax abatement, since properties using the abatement still pay taxes on land. If a new land tax rate is created and the balance of property tax rates shifts more toward land, that raises more property tax revenue from abated properties right away. This is an under-discussed alternative to the other abatement reform plans that have been floated so far, which only deal with as-yet-unbuilt properties, and it's especially interesting to look at now in light of what we might expect to be the interplay between Opportunity Zones and land values in the included areas.

Fix the Land Bank

One of the first things the City does should be to identify which publicly-owned properties are currently in Opportunity Zones, and making a plan for their highest and best use to deliver the greatest and most broadly-beneficial economic impact.

As the authors say:

"Each city should inventory property it owns, identify which entity owns it, and who has an interest in its use across each level and type of government. In addition to occupied buildings, cities, counties, states, and the federal government often own significant amounts of a city’s vacant land, as well as vacant properties that have been foreclosed on or are otherwise abandoned. Creating transparency among public entities is necessary to determine the value of all public assets, both to the public and potential investors— not just to whichever government entity happens to own them...Priority should be given to completing outstanding foreclosure processes, identifying LLCs and their registered agents as necessary, and clearing titles."

After a master property ownership list is created, it should serve as the basis for a local conversation about the actual highest and best use for each property in that community. For example, a vacant lot being held by a school development authority might be better suited to meeting a neighborhood need for housing, workforce development space and, perhaps, a school as well [..."

The Land Bank is right now working on a strategic plan that will guide the acquisition, disposition, and public redevelopment of all our publicly-held properties, and their analysis of the highest-and-best use for public land should now factor in the presence of an Opportunity Zone, and opportunities for redevelopment, particularly in strong market areas. As in the given example, we should be looking at all publicly-held properties differently in these zones, not just the ones that have been placed in the Land Bank so far, like municipal parking lots, for example. We know that on the whole, these lots are in all likelihood a lot more valuable than OPA says, and if they're in Opportunity Zones, the opportunity cost of using them for unpaid parking is even greater.

All throughout the city, we should take an especially close look at public properties within Opportunity Zones, and examine whether they could be used in ways that could be generating more jobs or public value.

How do you think local government should plan for these new Opportunity Zones? Read the report and share any observations or reactions in the comments.

Showing 1 reaction

Sign in with

Facebook