(Image: Jonathan Tannen, Sixty-Six Wards)

One of the more interesting features of the Sixty-Six Wards data portal is the attempt to quantify Philadelphia’s different voting blocs, which for these purposes are divisions—not people—that tend to prefer the same groupings of candidates across elections.

What’s most interesting about this is that, especially when it comes to Democratic primaries, there are some clear “parties” within the party that have some pretty clear candidate preferences over time, and knowing the exact divisions where those sub-parties tend to be strongest is very useful election information.

This week Jonathan Tannen of SSW wrote about a new dimension he is introducing into his 4-part classification system of Black Voters, White Moderates, Wealthy Progressives, and Hispanic Voters, which is a shift in demographic boundaries over time. Read the post for some insights on the ways in which these boundaries have shifted, as well as some of the candidate groupings as they relate to some of the different political and demographic axes in Philadelphia elections.

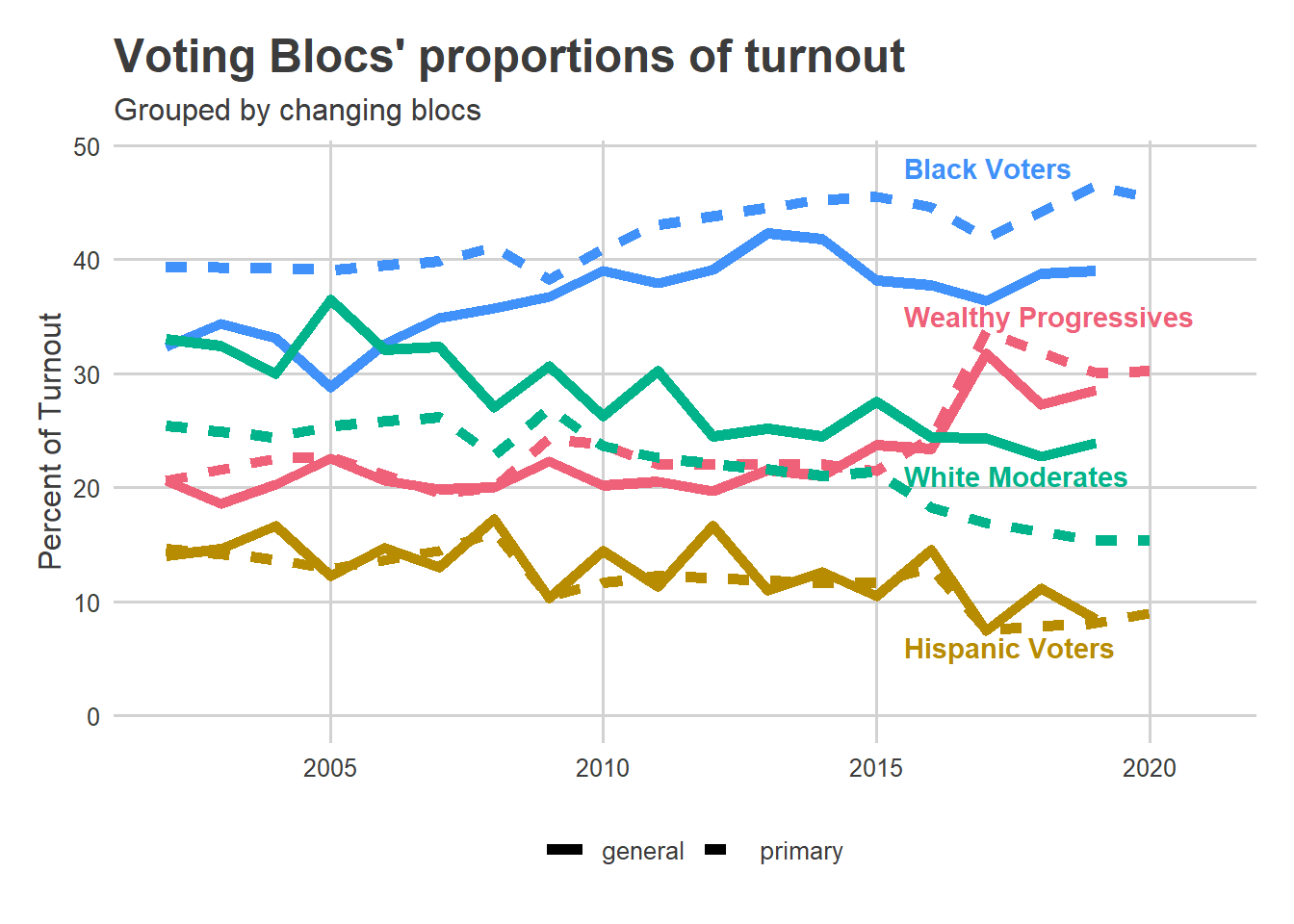

According to Tannen, the introduction of voting bloc boundary changes makes certain developments we’ve known about appear much more pronounced than previously thought, including the rising Black share of the primary vote in elections since 2002, and the 2017 level-jump for Wealthy Progressive divisions after that bloc first surpassed the White Moderate divisions’ vote share in 2015.

In the maps above, you can clearly see the expansion of the Wealthy Progressive divisions outward from Center City, and growth of the Black Voter divisions in North and West Philly, along with a shift in the Hispanic Voter divisions eastward and up into the lower Northeast.

With the moving boundaries, the changes in Blocs’ share of the vote is even starker than before.

Black Voters have seen an increasing share of the turnout since 2002, though that’s somewhat mitigated by changes since 2016. Wealthy Progressive share took a clear leap in 2017 and after. White Moderate and Hispanic Voter shares have seen a steady decline since 2002. Notice that this is not directly applicable to people; this is all traits of divisions.

Information like this will figure in a big way when it’s time to talk City Council redistricting and state redistricting, as lawmakers try to find ways to inoculate themselves against these voting bloc boundary changes by shedding divisions from voting blocs more likely to support a challenger. Watch this space for more on state and City Council redistricting, starting right after the 2020 Census data release.

Showing 1 reaction

Sign in with

Facebook