Now that the American Rescue Plan has been passed, the Biden administration is intent on pivoting to a big infrastructure package to the tune of $2 trillion. On Wednesday, Biden lifted the embargo on the American Jobs Plan, which laid out some very ambitious goals for infrastructure that, if adopted, could have some major positive impacts for Philadelphia’s economy, its built environment, and even the local politics of transportation and housing.

The plan calls for a more than $2.3 trillion investment across many sectors of the economy, including transportation, housing, energy, water, ports, the electrical grid, broadband, the care economy, and clean energy R&D. In addition, it proposes several important shifts in how the money would be spent that could hopefully lead to some important changes to the conditions under which this is all carried out by state and local governments—often the most important actors in the current system. There isn’t a detailed jobs projection yet, but Biden said in Pittsburgh that “Wall Street economists” estimate it could create as many as 18 million jobs.

Members of Congress will undoubtedly put their own spin on the bill, especially when it comes to earmarks, but the Biden administration is also coming with some big priorities too, and on first pass, there are several in particular that are worth paying attention to from a Philadelphia vantage point.

Transportation

The Biden plan calls for $621 billion for transportation funding, with a priority for maintenance, safety, and transit projects. The plan proposes more combined funding for rail and transit than it does for highways, which would be a major departure from past transportation bills.

Notably, the plan doesn’t call for new road capacity—something transportation reformers have been watching for—and instead prioritizes repair of existing roadways. Reformers often refer to this as a ‘Fix It First’ policy, a term used several times publicly by U.S. DOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg. The upshot of this policy would be to limit the amount of money that can be spent on vastly more expensive new road construction, and free up more funding for repairing existing infrastructure, making transit investments, and investing in street safety improvements to existing roadways.

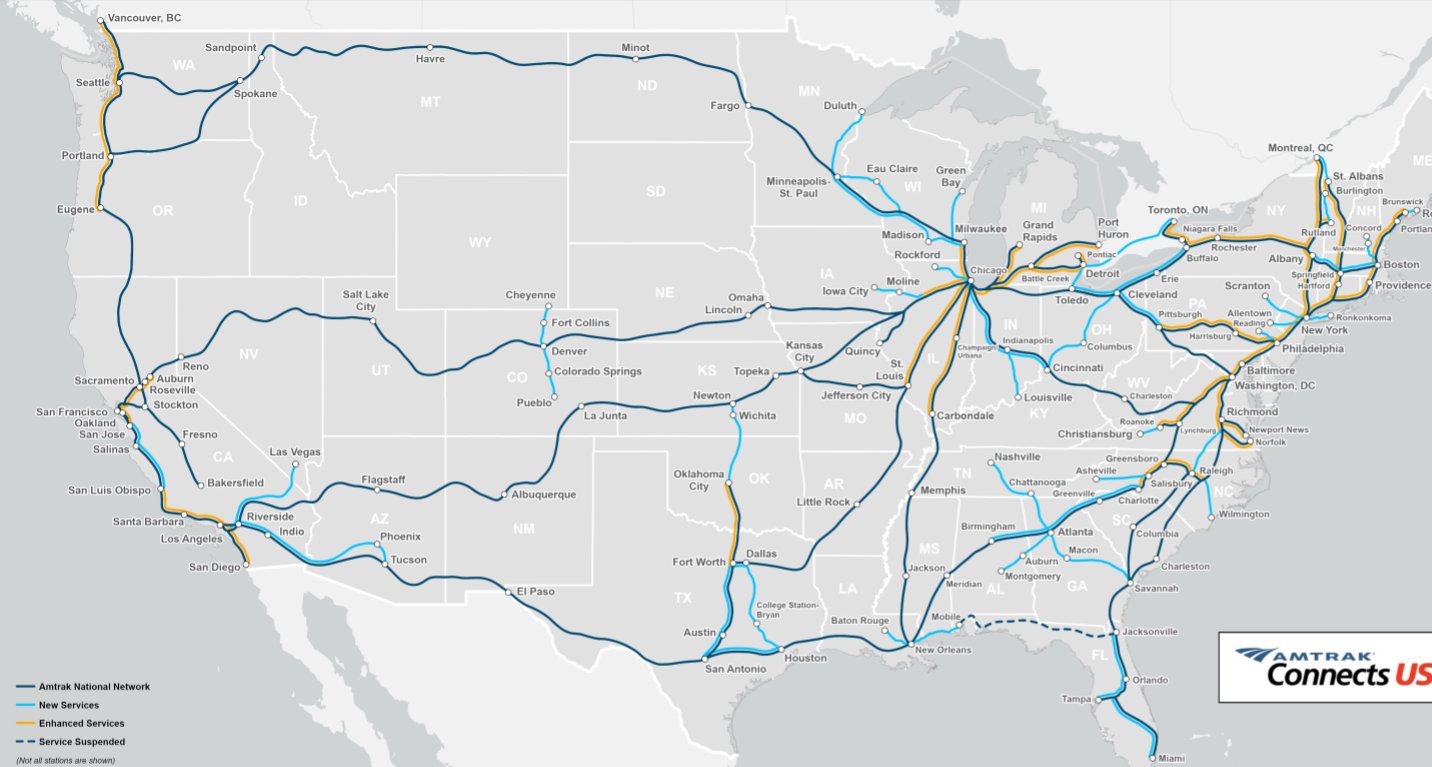

(New Amtrak map just dropped | Image: Amtrak)

To that end, the plan includes $115 billion in “Fix It First’ funding for roads, $85 billion for transit (double the current federal allocation), $80 billion for intercity rail, and $174 billion for electric vehicles and related infrastructure. The plan also calls for $20 billion for “complete streets” funding for multi-modal projects, bike and pedestrian improvements, and the like.

Vision Zero and Multi-modal Streets

On the last point, the lack of funding for a faster roll-out of complete streets and ‘Vision Zero’ projects (aimed at achieving the Mayor’s stated goal of zero traffic deaths or serious injuries by 2026) has often been a convenient excuse for local elected officials who may not support these kinds of street changes for other reasons, like parking and perceived inconvenience to drivers.

That’s one of the themes to watch from Philadelphia throughout the document: federal goals crashing into local politics. As Mayoral administrations pursue more complete streets projects, there’ll be more opportunities for conflict with some of the Councilmembers with more conservative views on transportation, like Council President Darrell Clarke, over the particulars. Is Council going to emerge as an obstacle for the Mayor to try and win more federal funding for projects to make streets safer? More funding is going to bring some more of this type of governance dysfunction to the fore and make it more visible.

Transit

The proposed transit funding increase to $85 billion would be a massive change, about doubling the current federal spend on transit. It’s still unclear whether the money will be allowed to be used for operations as well as capital projects, but it would be a big deal either way. There’s also another $80 billion proposed for building or increasing capacity of intercity rail networks to increase connections between cities.

According to the White House fact sheet, "[t]his investment will double federal funding for public transit, spend down the repair backlog, and bring bus, bus rapid transit, and rail service to communities and neighborhoods across the country,"

This is another area where local and state officials could really bungle this opportunity badly for the Philadelphia region if they don’t get with the program.

For example, this week it was reported that State Senator Anthony Williams and 2nd District Councilmember Kenyatta Johnson are working to award a massive piece of land in Southwest Philadelphia to Amazon that SEPTA desperately needs for a facility for their trolley modernization program. Trolley modernization is the City of Philadelphia’s top transportation infrastructure request to the federal government as part of these upcoming infrastructure and surface transportation packages, along with King of Prussia Rail. It’s also a critical maintenance project that must be funded in order for anything else to be funded, so it’s important that this gets done to enable all of SEPTA’s other projects.

An Econsult analysis from 2020 estimates the trolley modernization project would support about 38,000 jobs throughout the region, but Williams and Johnson are focused on the roughly 100 jobs that the Amazon facility would bring to the district. It’s a tough issue, but one where the stakes are much higher than the elected officials may realize, and if their plan goes through, they’ll jeopardize the one large federal project that would deliver the most benefits to Philadelphia residents out of any now under discussion.

On the operations side, national transit advocates and transit agencies have been asking Congress for $20 billion a year in operations funding, which would be enough to provide all transit systems with levels of service about equal to Chicago’s. This proposal falls short of that, but there will be another opportunity for a bite at the apple this fall when the surface transportation authorization law is set to expire.

The surface transportation reauthorization should add an additional $60 billion a year, or $300 billion over 5 years, to the total. And it will also provide another opportunity to attempt additional policy reforms as well.

Read Transportation for America’s analysis for the definitive transportation reform wonk take on the transportation piece of the proposal.

Electric Vehicles

Biden’s plan would also provide a significant boost to vehicle electrification, both on the public sector side and the private sector. The Biden administration aims to boost the electric vehicle industry by spending $175 billion to provide point-of-sale rebates and other tax incentives to electric vehicle buyers. It would also create new grant and incentive programs for state and local governments, and for the private sector to build out a network of chargers. The plan would also create a new Clean Buses for Kids program that would electrify more than 20 percent of the school bus fleet.

Philadelphia elected officials famously scrapped the city’s existing electric charging program for curbside charging after a few people complained, and replaced it with nothing. It’s unclear that there is another better option out there than curbside charging in a dense city environment, and Council hasn’t identified anything yet. But if the money becomes available for infrastructure and electric vehicle adoption increases, the local charging station siting politics are going to come back to force the issue.

Housing

The housing section of the plan has a lot to like, with proposals to produce 1 million affordable, energy-efficient housing, build and rehabilitate 500,000 middle-income and low-income homes meant for homeownership, and address long-standing maintenance backlogs for public housing.

One of Biden’s big housing agenda items from the campaign—making Housing Choice Vouchers an entitlement that everyone who is eligible for can receive—wasn’t part of this package, but could be introduced later as part of his budget.

Maybe the most intriguing part of the housing section is the proposal under “Eliminate exclusionary zoning and harmful land use policies” where the administration proposes to create a new “Race to the Top” type of competitive grant program that would only be available to jurisdictions that eliminate “needless barriers to producing affordable housing.” Among the barriers that they call out specifically are “minimum lot sizes, mandatory parking requirements, and prohibitions on multifamily housing” which would require some Philadelphia politicians to reconsider some of their most cherished regressive housing policies.

One thing the administration should consider is making the relevant jurisdictions for this be state governments specifically, rather than just cities, in order to give a political leg-up to more of the campaigns for state-level zoning reform that are increasingly gaining steam around the country.

If municipalities were the applicants, it’s an open question whether City Council would be open to applying for the grant. Bucking the emerging national consensus that more liberal zoning is a necessary but insufficient component of any housing affordability strategy, several powerful Philadelphia politicians have been going in an opposite, more reactionary direction, especially on things like lot sizes, parking, and apartment bans.

It’s possible a new pot of federal money could change some minds. But what would be even more effective would be for Pennsylvania lawmakers to require more liberal zoning from municipalities, rather than finding round-about ways of incentivizing this. Local zoning powers are derived from state government in the first place, and there are quite a few ways in which local land use powers are already shaped or constrained by the Commonwealth. When Congress passes the surface transportation reauthorization, they might want to consider tying eligibility for federal transportation funds to states making these changes, and amending their zoning enabling laws to strike policies the federal government deems exclusionary.

Will It Pass Congress?

There are so many great state and local changes that could come about because of the power of the federal purse in these major infrastructure negotiations, but just because Joe Biden is a Democrat doesn’t mean all his party members in blue states and cities are all on board with the Biden wishlist. It’s going to take smart policy design from the Biden administration, members of Congress, and their staff, to make sure the President’s very admirable goals aren’t dashed by guardians of the status quo in these lower governments.

Passing humongous federal legislation like this has gotten very difficult over the last decade for many reasons, mainly because of divided government, and the overabundance of veto points in the system where members of Congress are empowered to gum up the works.

But infrastructure and transportation have been areas of politics where Democratic and Republican members aren’t as far apart politically as they are on some other issues, and there’d even been some quiet progress on this around the surface transportation reauthorization bill in Congress during the Trump years. But it all falls apart when it comes to actually paying for infrastructure, because of the Republican Party’s stubborn anti-tax stance, so nothing’s gotten done. It also requires sustained attention from the President, which wasn’t something Donald Trump wasn’t ever able to provide, despite all the declarations of “Infrastructure Week”, which had become a punchline even by the early days of the Trump administration.

Biden’s infrastructure push seems more likely to work out for a variety of reasons. First, unified Democratic control of government gives the party’s legislative leadership a lot of power to put issues on the agenda, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York has some very strong home-state incentives to pass an infrastructure bill to save New York City’s transit systems, and to restart projects like the Gateway tunnel between New York and New Jersey. Additionally, the federal surface transportation authorization is set to expire in October and needs to be reauthorized in order to keep the country’s transportation systems funded. Earmarks are also back, which makes it much easier to pass major legislation since members have some better incentives to fight for home-district projects and try to reach a deal.

One wrinkle is that Pennsylvania Senator Bob Casey has said he doesn’t want to see an infrastructure bill pass via the budget reconciliation process, which would allow it to pass only with 51 Democratic votes. Casey would prefer a major package like that be bipartisan and include Republicans. But other Democratic Party leaders on the relevant committees have said they believe passing any infrastructure package of significant size will have to go through reconciliation in order to supply funding at the levels President Biden and others are calling for.

If the bill only needed 51 votes to pass, that would place Democratic Senators Joe Manchin and Krystin Sinema around the relevant veto point to determine what happens. And Manchin has made it known that he will support a very large multi-trillion dollar infrastructure package if it’s paid for with taxes, rather than deficit spending.

Having Manchin, rather than a much more conservative Republican senator, be the ultimate decider also matters greatly for the policy content of the infrastructure package. It would be an incredible missed opportunity if the federal government made a generational $3-4 trillion investment in upgrading the nation’s infrastructure but that spending did not make a transformative impact on things like climate change, renewable energy deployment, the transition away from fossil fuels, sustainable transportation and housing reform, and many other overlapping areas that sit more squarely within the Democratic coalition’s agenda. But all these changes would be much harder to pass if the relevant veto point sits at 60 votes instead of 51 votes, so reconciliation seems likely.

Democrats will likely only get one opportunity this decade to shape a major infrastructure and transportation package, and it’s happening while they have a trifecta in Congress and the Presidency. They should do all they can to make the most of it.

Stay in the loop on this topic and more by signing up for Philadelphia 3.0's weekly email newsletter

Showing 1 reaction

Sign in with

Facebook